Burning the Books: A History of the Deliberate Destruction of Knowledge by Richard Ovenden does an excellent job at demystifying the stories behind the burning of the library of Alexandria. It makes a compelling argument that equally contributing to the demise of the legendary library was neglect and a deprioritization of knowledge in the society where the library was located.

Ovenden splits the book into two main areas of focus, libraries and archives. I found this interesting since I have never really given much thought to archives and their importance in preserving culture and histories. I did find that the author, after making a clear distinction between the two and noting that they are not mutually exclusive, then starts to use the terms interchangeably toward the last third of the book.

The chapters on the Yugoslavian war of the nineties and the destruction of Jewish libraries during World War II are insightful and a warning to all that take such events lightly. These chapters shed light on how burning libraries and archives is a deliberate tactic that often time precedes genocide.

I found two problems with the book that irritated me:

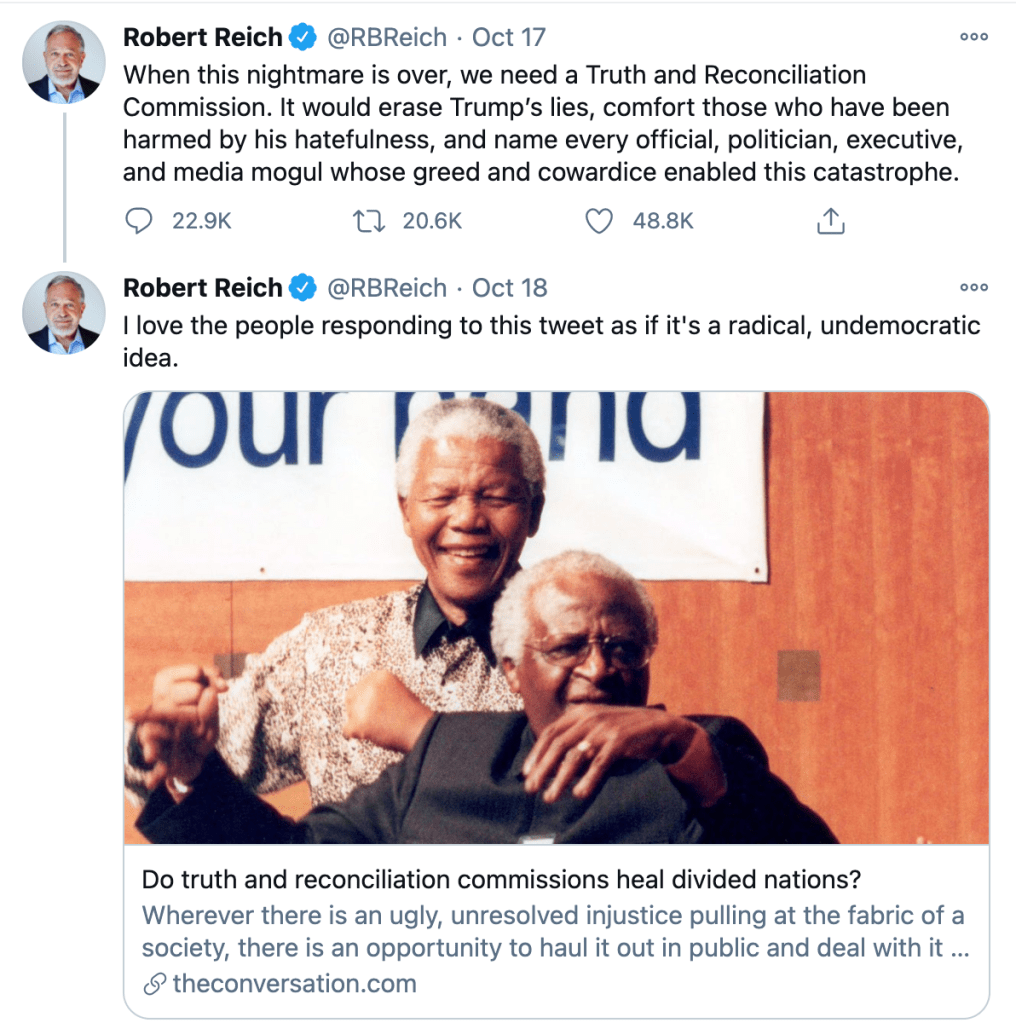

First, towards the end of the book, the author focuses on the importance and need to archive as much of the social media content as possible and frames this need as a duty for future generations. I am skeptical of this premise. I understand and can see the insights that such an initiative can provide to future generations on how we think and what our priorities may or may not have been. But I also find the idea of creating repositories of such large volumes of commentary rubbish dangerous. Social media platforms give everyone a voice, and an exceeding majority of people tend to regret a lot of what they say. Achieving such moments can be embarrassing and dangerous to people in the future. Just recently, former Labor Secretary Robert Reich called for making a list of Trump supporters so that the country can embark on a series of truth and reconciliation hearings. And while national archives can serve as powerful tools for justice, the other side of that blade can serve as an instrument for prosecution for past opinions or support. Ovenden does not even admit a negative side to such archiving, which I found troubling. Is this omittance naivety or deliberate ignorance on his part?

Second, Ovenden does a good job bringing to light how many Europes libraries, including the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford, have items on their catalogs that were acquired due to war and pillage. And while he seems to denounce the practice, he stops short of calling for the return of such items to their sources of origin. I found it rather annoying that he would bring the matter up but not offer his opinion. The case of manuscripts, works of art, and treasures acquired through imperialism and colonialism is a pressing matter that will gain momentum as more countries industrialize and move out of poverty. If western institutions had to return said collections, their museums and net value would plummet overnight. And while many of these institutions refraining from stating that they can care for these artifacts better than the people from where they originate (it would not be the politically correct commentary), their silence on the matter of what to do makes it clear that their liberal thinking only goes so far. I think that technology holds the key to preserving copies of these artifacts and making them accessible to the world at large.

While I have noted two issues that bother me about Burning the Books, I still think the project is well written, and its author is an accomplished scholar. This book should be in any bibliophile’s collection.