On January 2nd, Bloomberg published a piece titled “Nobel Prize Winner Cautions on Rush into STEM After Rise of AI.” Now, I have been struggling with this article and its overall message of “don’t study STEM,” it has taken me a while to process it because I wanted to be nice about it, but I was having a hard time doing so. The Nobel Prize-winning economist mentioned is Christopher Pissarides, and essentially, he says that people should not be studying STEM anymore because “This demand for these new IT skills, they contain their own seeds of self-destruction.” Instead, he suggests that people should develop skills for “jobs requiring more traditional face-to-face skills, such as in hospitality and healthcare.”

So, why does this bother me?

Experts get things wrong all the time. And for someone of Pissarides’ stature to make such a recommendation exemplifies his lack of understanding of this new and dynamic field. Furthermore, it spreads fear around AI and its inevitable destruction of the human labor force.

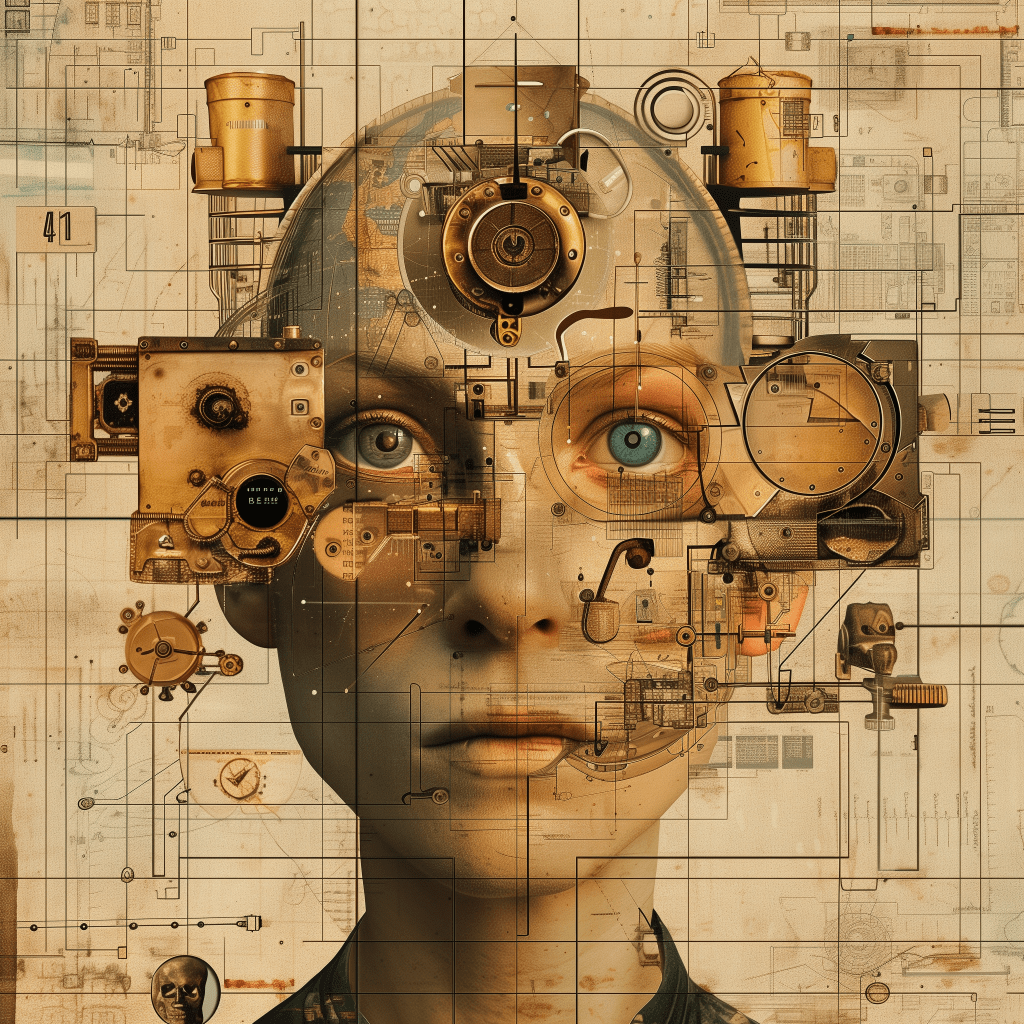

There is so much that we don’t know about AI. Even the so-called experts in the field can’t fully explain what’s happening or why it’s (AI systems) doing what it does. We have an idea now about how and why hallucinations happen, but it was not something anyone predicted. And while we are working hard to eliminate or minimize them, we might not be able to eliminate it completely. Every week, a new paper shows some kind of anomaly or strange effect that is inspiring, bizarre, or frightening.

Contrary to what this Nobel Prize-winning economist says, I argue that now more than ever, there is the time for people to double down on STEM studies, particularly in fields like computer science, data science, cognitive science, and ethics. We are living in a golden age of technology, and we need more people with diverse backgrounds, interests, and ideas and less of the tunnel vision, institutionalized, and narrow-scope mentality from Silicon Valley. We need more folks from China, Japan, Russia, India, Africa, and Latin America to challenge its echo chambers. It’s not that one should replace the other; we all have a stake in this game. We need people from all walks of life and all industries to weigh in on these technologies and their implications. The study of philosophy has been in decline for decades, and now more than ever, we need people to revisit this subject and become part of the dialog.

Author David Epstein, who wrote the book “Range: Why Generalist Triumph in a Specialized World,” noted on the “World of DaaS” podcast that research has shown that experts get things wrong more often than generalists. Epstein specifically references Philip Tetlock’s book “Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?” published in 2005. The research suggested an inverse relationship between fame and accuracy, meaning that the more famous some experts are, the more they get things wrong. That’s problematic because we listen to these experts, and yet they get a lot more airtime, creating a vicious cycle of wrong forecasting and an audience that is misled. But when these experts’ predictions/forecasts are measured, as Tetlock’s book did, you find that they get things wrong more than they do right.

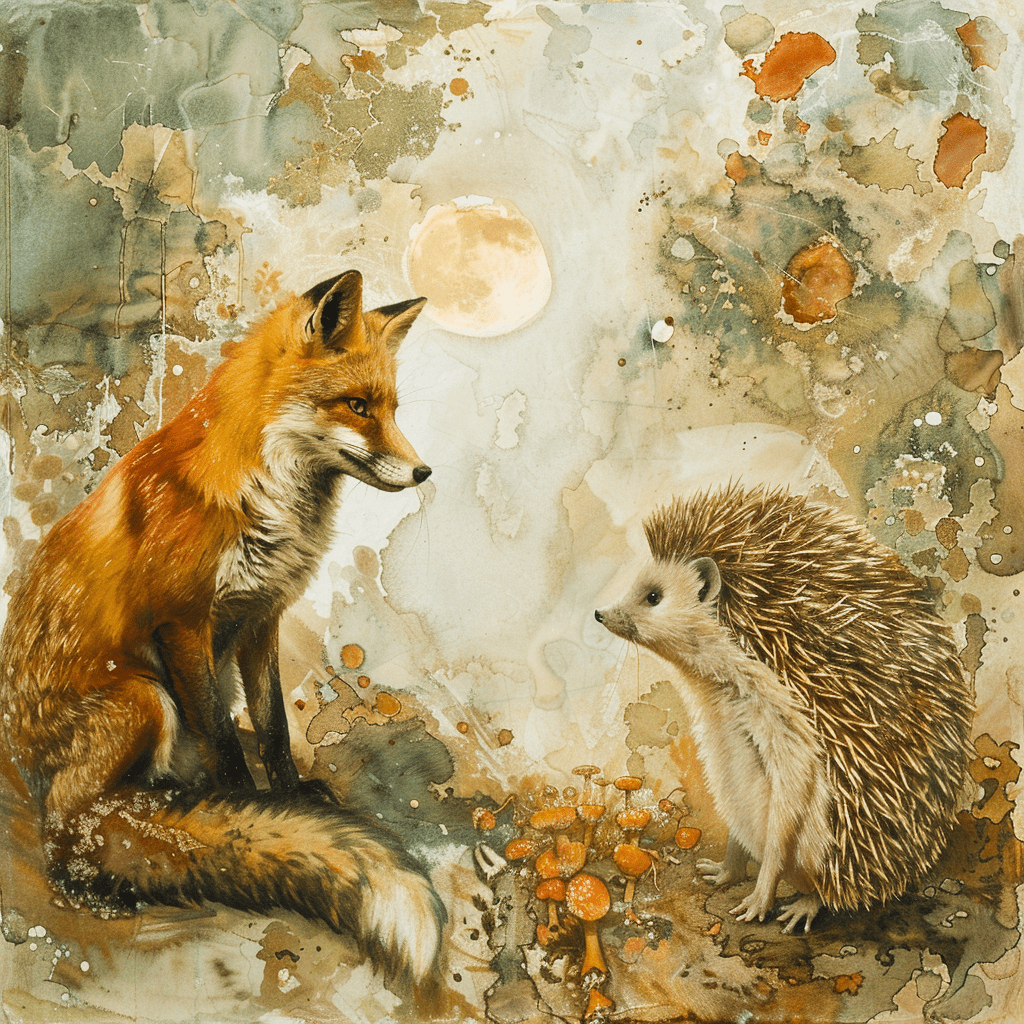

Tetlock divided his subjects into two groups, foxes and hedgehogs, where a “fox” is defined as a thinker who knows many things, is skeptical of grand theories, adaptable, and ready to adjust ideas based on actual events, while a “hedgehog” knows one big thing, adheres to a grand theory, and expresses views with great confidence. Below is a summary of the top five findings of the research:

1. Foxes, use a diverse range of experiences and are adaptable in their thinking, consistently outperform hedgehogs, who focus on grand theories, in forecasting accuracy.

2. Foxes’ superior predictions are due to their diverse thinking and openness to various perspectives, while hedgehogs’ adherence to singular theories hampers their forecasting ability.

3. Calibration and discrimination are better in foxes, enabling them to align prediction probabilities with actual outcomes and make nuanced assessments of their confidence levels.

4. Foxes’ willingness to learn from their mistakes, reflected in their self-critical reflection and belief updates, contrasts with hedgehogs’ tendency to rationalize or dismiss contradictory evidence.

5. Open-mindedness, a critical factor in foxes’ success, highlights the importance of fostering openness and cognitive flexibility to enhance individuals’ forecasting abilities.

Paul Krugman’s 1998 prediction about what the internet would look like in seven years is an example of hedgehog thinking that I never tire of highlighting. Note that he is also a Nobel Prize-winning economist. Krugman stated:

The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’-which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants—becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.

Paul Krugman, 1998

Now, sit and dwell on that for a minute. This was an expert. A future Nobel Prize-winning economist (Krugman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2008). Krugman is responsible for a series of predictions that never came true, yet he is never held accountable and is a fan favorite of the news outlets.

So, why do we need more people to study STEM? Simply put, we don’t know as much as we’d like to think we do.

I am a fan and supporter of AI; I don’t fear it. But I do fear the hubris with which we are approaching this technology and its macro and micro implications. I do not want to outsource its regulations and development to Silicon Valley, Government, or “experts.” All of which think that consolidating and centralizing control in the name of safety is a good idea, I disagree. Comments like those by Mr. Pissarides, encouraging people to stay away from STEM studies, are irresponsible and unhelpful, feeding into fears that people will become useless in some fields.

Complex systems, especially AI systems of a generative nature, exhibit emergent behavior. This feature alone should be a reason for wanting more people to study STEM, particularly in fields that can help us better understand, align, and explain these systems, such as:

- Computer Science and AI/ML to advance the technical underpinnings

- Cognitive Science and Psychology to model and align with human cognition

- Philosophy and Ethics to grapple with the moral implications

- Social Sciences to study the societal impacts

- Domain experts (healthcare, law, education, etc.) to guide application

Here are a couple of things that give me hope and why we need more people to study these areas:

1. AI can make accurate predictions but focus on irrelevant data features, which raises questions about its trustworthiness — because the rationale behind these decisions remains unknown and challenging.

2. Deep learning AI systems are often considered “black boxes,” making it difficult to trust their decisions in critical applications — lack of transparency of these processes is problematic.

3. The AI alignment problem, ensuring that AI systems’ goals align with human intentions, especially in the context of superintelligent AI — misalignment can pose significant risk.

4. Explainability in AI systems remains a challenge, with efforts being made to improve transparency through more transparent machine learning models and interdisciplinary research.

The examples above are enough to start new, lucrative and rewarding fields of study. I don’t want the present and future generations to be myopic about the world of possibilities. And while the hype is that AI will become god-like, my take is that these systems will be powerful tools that will amplify the very best and worst in all of us.

No, I think this gentleman, Nobel Prize or not, is categorically wrong, and his comments are irresponsible. We need to push back on the rush to regulate and centralize AI and on experts who oversimplify how these systems work.

I’ll end with a quote by Karim Lakhani, a professor at Harvard Business School whose focus is on workplace technology:

“It is not that AI machines will replace humans, but that humans who use AI will replace those who don’t.”

Karim Lakhani

NOTE: Diverse thinking, as defined by Philip Tetlock’s research on superforecasters, refers to the practice of integrating multiple perspectives, knowledge sources, and cognitive approaches when analyzing problems or making predictions. This includes actively seeking out conflicting viewpoints and evidence to counteract confirmation bias, leveraging cognitive diversity within teams, and bringing together individuals from different fields and backgrounds in interdisciplinary teams. Additionally, cultivating creative behaviors such as an open mindset and the power of iteration can enhance forecasting abilities and innovation. By embracing diverse thinking, individuals and organizations can improve the accuracy of forecasts, foster innovation, and enhance the overall quality of decisions.

Previously posted on LinkedIn.