Tolerance will reach such a level that intelligent people will be banned from thinking so as not to offend the imbeciles — Anonymous

Tolerance will reach such a level that intelligent people will be banned from thinking so as not to offend the imbeciles — Anonymous

On January 2nd, Bloomberg published a piece titled “Nobel Prize Winner Cautions on Rush into STEM After Rise of AI.” Now, I have been struggling with this article and its overall message of “don’t study STEM,” it has taken me a while to process it because I wanted to be nice about it, but I was having a hard time doing so. The Nobel Prize-winning economist mentioned is Christopher Pissarides, and essentially, he says that people should not be studying STEM anymore because “This demand for these new IT skills, they contain their own seeds of self-destruction.” Instead, he suggests that people should develop skills for “jobs requiring more traditional face-to-face skills, such as in hospitality and healthcare.”

So, why does this bother me?

Experts get things wrong all the time. And for someone of Pissarides’ stature to make such a recommendation exemplifies his lack of understanding of this new and dynamic field. Furthermore, it spreads fear around AI and its inevitable destruction of the human labor force.

There is so much that we don’t know about AI. Even the so-called experts in the field can’t fully explain what’s happening or why it’s (AI systems) doing what it does. We have an idea now about how and why hallucinations happen, but it was not something anyone predicted. And while we are working hard to eliminate or minimize them, we might not be able to eliminate it completely. Every week, a new paper shows some kind of anomaly or strange effect that is inspiring, bizarre, or frightening.

Contrary to what this Nobel Prize-winning economist says, I argue that now more than ever, there is the time for people to double down on STEM studies, particularly in fields like computer science, data science, cognitive science, and ethics. We are living in a golden age of technology, and we need more people with diverse backgrounds, interests, and ideas and less of the tunnel vision, institutionalized, and narrow-scope mentality from Silicon Valley. We need more folks from China, Japan, Russia, India, Africa, and Latin America to challenge its echo chambers. It’s not that one should replace the other; we all have a stake in this game. We need people from all walks of life and all industries to weigh in on these technologies and their implications. The study of philosophy has been in decline for decades, and now more than ever, we need people to revisit this subject and become part of the dialog.

Author David Epstein, who wrote the book “Range: Why Generalist Triumph in a Specialized World,” noted on the “World of DaaS” podcast that research has shown that experts get things wrong more often than generalists. Epstein specifically references Philip Tetlock’s book “Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?” published in 2005. The research suggested an inverse relationship between fame and accuracy, meaning that the more famous some experts are, the more they get things wrong. That’s problematic because we listen to these experts, and yet they get a lot more airtime, creating a vicious cycle of wrong forecasting and an audience that is misled. But when these experts’ predictions/forecasts are measured, as Tetlock’s book did, you find that they get things wrong more than they do right.

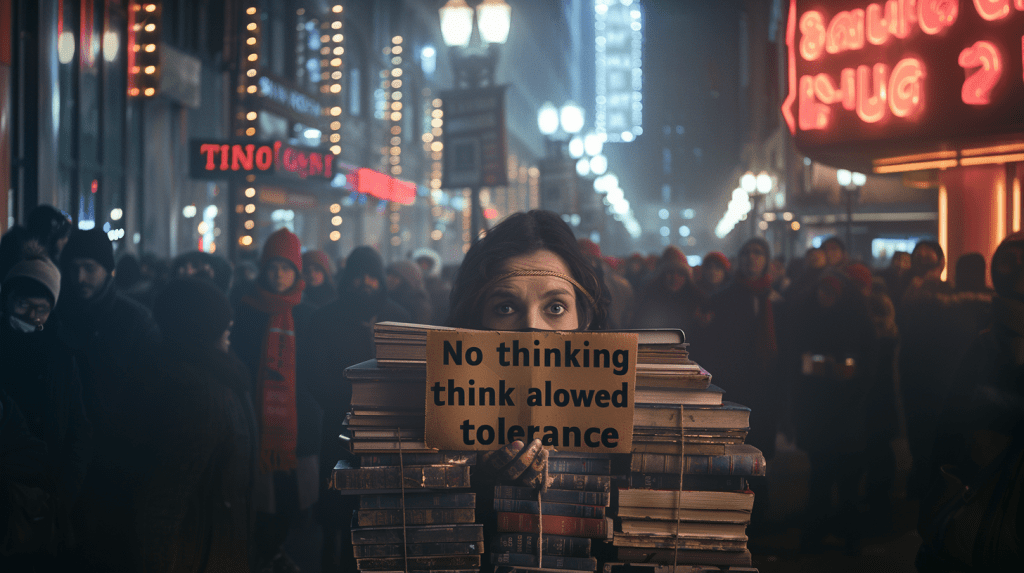

Tetlock divided his subjects into two groups, foxes and hedgehogs, where a “fox” is defined as a thinker who knows many things, is skeptical of grand theories, adaptable, and ready to adjust ideas based on actual events, while a “hedgehog” knows one big thing, adheres to a grand theory, and expresses views with great confidence. Below is a summary of the top five findings of the research:

1. Foxes, use a diverse range of experiences and are adaptable in their thinking, consistently outperform hedgehogs, who focus on grand theories, in forecasting accuracy.

2. Foxes’ superior predictions are due to their diverse thinking and openness to various perspectives, while hedgehogs’ adherence to singular theories hampers their forecasting ability.

3. Calibration and discrimination are better in foxes, enabling them to align prediction probabilities with actual outcomes and make nuanced assessments of their confidence levels.

4. Foxes’ willingness to learn from their mistakes, reflected in their self-critical reflection and belief updates, contrasts with hedgehogs’ tendency to rationalize or dismiss contradictory evidence.

5. Open-mindedness, a critical factor in foxes’ success, highlights the importance of fostering openness and cognitive flexibility to enhance individuals’ forecasting abilities.

Paul Krugman’s 1998 prediction about what the internet would look like in seven years is an example of hedgehog thinking that I never tire of highlighting. Note that he is also a Nobel Prize-winning economist. Krugman stated:

The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’-which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants—becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.

Paul Krugman, 1998

Now, sit and dwell on that for a minute. This was an expert. A future Nobel Prize-winning economist (Krugman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2008). Krugman is responsible for a series of predictions that never came true, yet he is never held accountable and is a fan favorite of the news outlets.

So, why do we need more people to study STEM? Simply put, we don’t know as much as we’d like to think we do.

I am a fan and supporter of AI; I don’t fear it. But I do fear the hubris with which we are approaching this technology and its macro and micro implications. I do not want to outsource its regulations and development to Silicon Valley, Government, or “experts.” All of which think that consolidating and centralizing control in the name of safety is a good idea, I disagree. Comments like those by Mr. Pissarides, encouraging people to stay away from STEM studies, are irresponsible and unhelpful, feeding into fears that people will become useless in some fields.

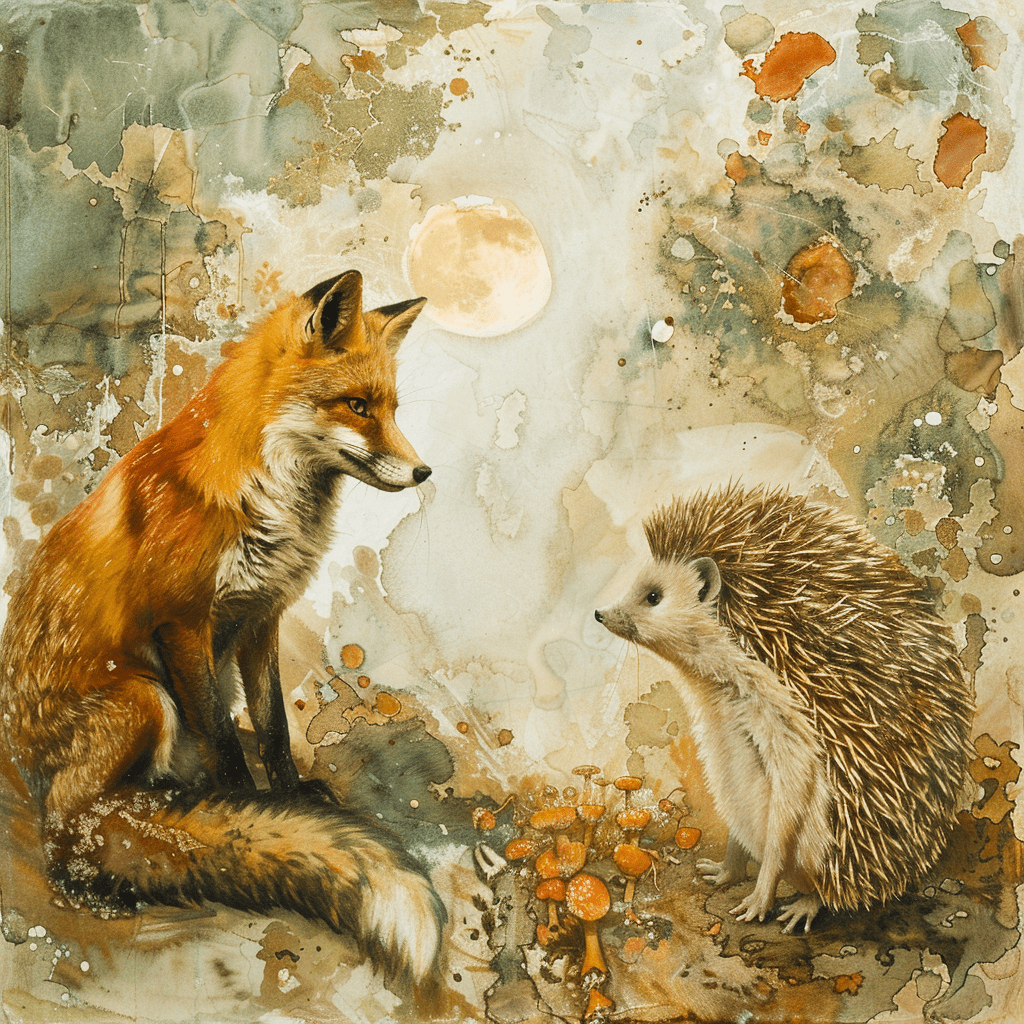

Complex systems, especially AI systems of a generative nature, exhibit emergent behavior. This feature alone should be a reason for wanting more people to study STEM, particularly in fields that can help us better understand, align, and explain these systems, such as:

Here are a couple of things that give me hope and why we need more people to study these areas:

1. AI can make accurate predictions but focus on irrelevant data features, which raises questions about its trustworthiness — because the rationale behind these decisions remains unknown and challenging.

2. Deep learning AI systems are often considered “black boxes,” making it difficult to trust their decisions in critical applications — lack of transparency of these processes is problematic.

3. The AI alignment problem, ensuring that AI systems’ goals align with human intentions, especially in the context of superintelligent AI — misalignment can pose significant risk.

4. Explainability in AI systems remains a challenge, with efforts being made to improve transparency through more transparent machine learning models and interdisciplinary research.

The examples above are enough to start new, lucrative and rewarding fields of study. I don’t want the present and future generations to be myopic about the world of possibilities. And while the hype is that AI will become god-like, my take is that these systems will be powerful tools that will amplify the very best and worst in all of us.

No, I think this gentleman, Nobel Prize or not, is categorically wrong, and his comments are irresponsible. We need to push back on the rush to regulate and centralize AI and on experts who oversimplify how these systems work.

I’ll end with a quote by Karim Lakhani, a professor at Harvard Business School whose focus is on workplace technology:

“It is not that AI machines will replace humans, but that humans who use AI will replace those who don’t.”

Karim Lakhani

NOTE: Diverse thinking, as defined by Philip Tetlock’s research on superforecasters, refers to the practice of integrating multiple perspectives, knowledge sources, and cognitive approaches when analyzing problems or making predictions. This includes actively seeking out conflicting viewpoints and evidence to counteract confirmation bias, leveraging cognitive diversity within teams, and bringing together individuals from different fields and backgrounds in interdisciplinary teams. Additionally, cultivating creative behaviors such as an open mindset and the power of iteration can enhance forecasting abilities and innovation. By embracing diverse thinking, individuals and organizations can improve the accuracy of forecasts, foster innovation, and enhance the overall quality of decisions.

Previously posted on LinkedIn.

In General H. R. McMaster’s book, Battlegrounds: The Fight to Defend the Free World, the general notes that the Korean War, a conflict, which claimed the lives of millions and left no clear victor, serves as a poignant reminder of the grim consequences of armed conflicts. As we grapple with the potential dangers of the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict, it becomes crucial to examine why we selectively remember and romanticize certain lessons from history while neglecting others.

McMaster’s book brings forth the staggering human cost of the Korean War, presenting a grim account of lives lost and shattered. The numbers are harrowing: nearly 10,000 Americans, 200,000 South Korean and United Nations soldiers, 400,000 North Korean soldiers, 600,000 Chinese troops, and a devastating toll of 1.5 million civilians. The combined death toll amounts to approximately 3 million individuals, all victims of a war that ended in a stalemate, with neither side able to claim outright victory.

These figures emphasize the profound futility of war. Lives were destroyed, families torn apart, and entire communities decimated, all without achieving a decisive outcome.

The war between Russia and Ukraine threatens the stability of the region but also poses an existential threat to humanity itself. Yet, despite its potentially catastrophic consequences, it is mind-numbing to witness how this conflict fails to capture the same level of attention and concern as other global issues such as climate change or identity politics.

Perhaps it is the allure of triumphant narratives or the desire to highlight tales of heroism and resilience that helps distract us from the horrific consequences of a head-on confrontation with Russia. Ukrainian flag icons and Tweets of support allow us to outsource our decision-making to the experts. But the forgotten casualties, the shattered lives, and the irreparable damage inflicted on societies by these wars demand our attention and remembrance.

The Future of Life Institute has produced a sobering video on how a nuclear exchange between the nuclear powers – the United States and Russia – would unravel. Our news organizations should be focused on delivering this message to our populations and not on being the propaganda parrots for the foolish policies of the current administration and the US Congress’ immoral support of said policies.

Reading through this article from Politico where they state that millions of Americans will lose healthcare as a result of a clamp down on those that don’t need healthcare any longer, particularly those ago during the Covid era is really disturbing. I really think that when you look at the amount of money that were spending on this proxy war between Ukraine and Russia, the fact that we’re gonna have 15 million Americans – 5 million of those are children – losing healthcare is just as graceful as a country.

Personally, I’m not a big fan of big social programs, but I find it intellectually dishonest, and quite frankly offensive, that we can find money for a war that shows very little by way of being in the interest of the American people, but we can’t find that money to treat our folks with better healthcare, or better education or better programs.

Over the last few months, I have found myself grappling with the frustrations of flight delays. This week, a thought struck me, the airline industry’s predominant issue, in my observation, lies in its extensive consolidation and centralization around colossal hubs. This consolidation has resulted in a scenario where reaching most cities now requires connecting flights unless one is traveling between major urban centers. It appears that everything has been centralized, and these central hubs are a consequence of the federal government’s inclination to centralize every aspect of our lives. Centralization, despite its perceived efficiency, is far from ideal. Its vulnerability to disasters and catastrophes, coupled with the constant pressure on airlines, begs for a more decentralized approach.

Centralization is ill-suited to be resilient. Centralized systems, as many of us have experienced, are susceptible to calamities and crises.

Now contrast these centralized systems with nature. When a hurricane devastates a region or wildfires wreaks havoc, these environments have the ability to bounce back precisely because they are decentralized. Nature thrives on distributed architectures, and achieves a remarkable level of resilience.

Airlines, driven by the need to transport passengers from one place to another, are compelled to reassess their approach. Instead of relying solely on concentrated hubs, an alternative could involve a more distributed network of airports throughout the country. By doubling the number of airports and strategically spreading them across the nation, the potential for more connecting or direct flights between smaller cities and major hubs would increase significantly.

The drawbacks of centralization extend beyond the airline industry; they permeate other spheres of our lives, including politics and media. Over-centralization within politics, whether within the two major parties or the encroachment of the federal government on state and local jurisdictions, has diminished resilience. Our political system, as a result, lacks the ability to adapt and cater to the diverse range of opinions held by the majority of individuals. Furthermore, centralized media and other aspects of society contribute to the dominance of polarizing views, controlled by a minority, while the majority’s nuanced perspectives are overshadowed. Centralization proves detrimental to the robustness of our political, social, and informational landscapes.

Centralization poses significant challenges and disadvantages across various domains, including the airline industry. By acknowledging the inherent vulnerability of centralization and embracing a more distributed approach, we can foster resilience and efficiency. We need to embrace humility and learn from the wisdom found in the decentralized nature of the world around us, by designing systems that can withstand challenges — scaling and contracting as needed.

I’m fascinated by how much is out there regarding how fascism works. But almost nothing about how Communism doesn’t.

In a Wall Street Journal oped titled, Why Warren and Sanders Object to Crypto Rule, by Brian P. Brooks and Charles W. Calomiris, the authors, make a compelling argument for bringing the cryptocurrency sector into the supervised national banking system. Interestingly, while taking a jab at how risky the already regulated, supervised national banking system is. They theorize that the objection of staunch regulators like Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren to doing so is:

Here’s our theory: Crypto developers are trying to build a financial system where users have more control. In that system, credit is allocated by algorithms rather than loan officers, payments are settled instantly on blockchains rather than slowly inside the Federal Reserve, and customer funds are secured by cryptographic keys rather than by hackable debit-card PINs. A user-controlled financial system threatens the vision of a government-controlled system for which Sens. Warren and Sanders continue to advocate.

Why Warren and Sanders Object to Crypto Rules – WSJ: https://on.wsj.com/3CKD3uX

The authors go on to say that they agree with the current administration’s opinions on cryptocurrencies. And that the purpose of having a regulatory system is to “take risky financial activities for which there is high customer demand, and make them less risky.”

So, on the one hand, the system is not beyond risk, and regulations don’t eliminate, or for that matter, reduce risk — see 2008. And on the other hand, the system is there to help make these sectors “less risky.”

I read this as advocates for cryptocurrencies looking for legitimacy from the government. A legitimacy that would open the floodgates for major, “too big to fail” institutions to go wild with speculation and productizing for customers while hiding behind the safety net of the federal reserve.

For all the virtues and promises of decentralization, the cryptocurrency sector remains controlled by a very few. A few who will benefit immensely from the legitimacy regulation would lend it. The same few will have the funds and influence to use said regulation to lock out any potential newcomers or disruptors.

Perhaps banks and the federal reserve, in particular, may be taken out of the central role or, at a minimum, set to the sidelines. But all that data will need to run over something; those who control the network will control the economy.

Sometimes your calling doesn’t sync with other people’s plans for you. Their plans don’t matter if they don’t sync with your calling.

I moved to Miami back in March of this year. A big move. The result of the end of my marriage. I only knew two people in Miami at the time. So the move overall was hard given the drastic change in my home life, of which the hardest was leaving my 15-year-old daughter behind on the west coast — she was to live with her mom.

Its is a loneliness that manifest itself physically

Carolina

I can say that the most challenging part of the day for months was 5 pm through midnight. This time was the window right when work ended, and then there was nothing or no one. The loneliness was a loneliness I had never felt before. As someone I spoke to during that period brilliantly noted from her own experience, “It is a loneliness that manifests itself physically.” And it did. But the loneliness serves as a purification process for the soul, the mind, and the body. Introspection becomes an unwelcomed companion, and you have the choice to embrace it or reject it.

Months of introspection started to rebuild my sense of self. Fearing what I would find, I nonetheless proceeded forward — I had no choice. I can’t say I have arrived where I am going, but I am no longer bound by the chains of regret and hurt. And while the fear of the unknown always remains near, it has become more of an instrument than a blocker. A radar of sorts to help guide me on this journey. The more discomfort and fear, the more I know I should continue on the path and explore the whys of such feelings.